Point Zero

A walk from Thorne to Goole

A walk from Thorne to Goole, via the Stainforth and Keadby Canal, Keadby Wind Farm, the River Trent, the River Ouse and the Dutch River, 9.25pm Saturday 3 January to 9.25am Sunday 4 January.

I have a delivery to make, en route to Sheffield station, which lengthens the walk a little, 10 minutes, 20 minutes. The address is correct but the property is hard to locate. It is a new apartment complex near Decathlon. The signs don’t add up. Not this street. Not this block. Not this entrance.

A passing resident punches in the door code, then again, and again. It opens on the third attempt and I step into the lobby and walk to the wall-mounted mail lockers and post the parcel in a box that matches the apartment number on the address, then leave, unsure if this is the right building.

Bad signage. Bad lighting. Nothing to be done. Mary Street, Shoreham Street, Sheaf Street and the station. A single to Thorne from the self-service ticket machine. £8.20. Two trains. Seventy-four minutes, including a thirty-minute connection. Depart from platform 1b. Change at Doncaster.

8.13pm. The three-carriage train pulls out of the station, two minutes behind schedule, and I think not of the last time that I made this journey but of the time that has passed since I last made this journey. Six years and four months. How much of it spent waiting. Without ever stopping.

8.38pm. Doncaster. I disembark and scramble down the steps from platform 8 and into the underpass then resurface in the ticket hall and scan the departure boards. Delays. Cancellations. Northbound. Southbound. Half the network freezing up. I find the train to Thorne. 9.07pm. Platform zero.

I pace the edges of the ticket hall for twenty minutes or so then make my way to platform zero, which lies to the north of the main structure and is accessed via an elevated walkway from platform three, it is a terminal platform, built on the site of a former cattle dock. One way in, one way out.

9.02pm. The train appears, a few minutes ahead of time, three carriages, two conductors, empty when we board, half-full when we leave. Who would make this journey unless it was necessary. I message Emma, repack my rucksack, watch the one-sided moon slide in and out of the reflective glass.

A walk is an act of displacement. A walk is an act of attention. Are either of these things true? Wrong question. Can they both be true at the same time? Wrong question. Days, no, weeks of distraction, unrelenting distraction, the kind that you can’t outthink, the kind that you can’t outpace.

9.25pm. Thorne North. I disembark, along with three other passengers, and photograph the departing train, then take the steps down to the street, and set myself straight, from memory. Field Side for a third of a mile, a right turn onto Pinfold Lane, and all the houses still lit up for Christmas.

On Lock Lane I stop to take another photograph, then remember that the sixth generation iPad, which belonged to my late mother, and which is my only camera for this excursion, has no flash, and I have no torch. What is there to work with. Available light. Nothing more. One shot in focus.

The sign for Bunting’s Wood. The water must be close. William Bunting was a self-taught naturalist and entomologist who campaigned against the degradation of the area of lowland raised peat bog known as Thorne Moors, and successfully argued for the reinstatement of public footpaths on maps of the area.

After Bunting died in 1995, a 79-acre wood, south-west of Thorne, was named in recognition of his environmental activism. Twenty years later, it emerged that Bunting had abused two of his granddaughters as children. His name was removed from the maps, but not, as yet, from the streets.

Thorne Lock. It’s the only set of gates between Stainforth and Keadby: the landscape that the canal passes through is as flat as the water. I unbuckle my rucksack and take several photographs, each worse than the one before. Then silence. Stillness. The steps into darkness. Everything at zero.

The towpath east. I came here for the cold, and the cold is here, and there will be more cold to come. I will move with it and through it and towards it. Into morning. It’s a measure of time. How much can you stand. It’s not a test. Of endurance. Or will. I didn’t come here for answers.

I didn’t come here for punishment. I have dressed the body in layers, four on the trunk, two on the legs, thick socks that have yet to take shape, old boots, borrowed gloves, and, for perhaps the first time, a hat, a faux-fur trapper with ear flaps and chin strap. A gift from Emma.

9.50pm. Unblinking flare of riverside properties, spilling into empty gardens, searching the water, flooding the south bank. No motion sensors, trips or timers. Full glare. Dusk till dawn. It is hard to think with the blaze of LEDs. It is hard to read the path ahead.

A sharp, southerly turn. The swing bridge, the road bridge, the boatyard and marina. The scaled-down security features. Custom signs. Cabin lights and external downlights. Low, locked gates for each mooring, fenced against the path, dividing neighbour from neighbour. I keep my distance.

The railway bridge. Thorne South across the water and the path turning east. The glare softens and I can see the canal at my side and my steps as I take them. I thought that the moon would be enough, a full moon on a clear night, and it is, nowhere near its zenith, but all the light that I need.

Narrowboats on the north bank. Lights all the way to Wykewell Lift Bridge, or Peggy Fleckham’s Bridge, as it was known to a former resident of Thorne who filled in some of the blanks on a walk that I led in 2019. Her grandfather had picked up the name in 1910. No-one knew who Peggy Fleckham was.

10.15pm. It’s quiet now, quiet enough for me to hear the ducks astir in the south soak drain and, if I unfasten my hat and lift the ear flaps, what might be moorhens or coots. Moor Road Swing Bridge. Here I met a man who was taking his narrowboat to Nottingham, all the way south on the Trent.

10.20pm. A three-carriage train, just above the north soak drain, passing from west to east. To silence. Something has gone wrong with the body. I don’t know what it is. Something always goes wrong with the body in winter. Dental pain. Tendonitis. Tinnitus. Now this. Whatever this is.

It’s not pain. Not as such. Call it an ache. An ache that won’t shift. An ache that won’t stop. It could be anything. It might be nothing. It could be something. A small thing. And the space it takes up. 10.25pm. A three-carriage train, just above the north soak drain, passing from east to west.

Nun Moors to the north. I thought that the turbines might be visible by now, the lights of farmsteads in the foreground, all else forsaken, the horizon extinguished. The glare is good for making notes, an A4 sheet folded into eighths, the ink of a black Bic biro freezing in its reservoir.

10.37pm. The first few turbines, faint as greyscale, 50%, 40%, 30%. No reflective light. No colour contrast. Scarcely a breeze on the towpath but the rotation in the moorland is clear. Keep moving. Don’t stop. I loosen the flaps of my hat and listen to the blades scything the darkness.

Two swans on the water, one in the other’s wake, both gliding into the west. And all that I can’t see, only hear, in the soak drain. Everything is narrowing. To a distant point. The moon ahead and skewing to the south-east. Sirius. Or Jupiter. I pick out the line of the path through the grass.

10.45pm. First signs of frost underfoot. I’ve walked the Isle of Axholme at night only once before, in 2017, a few weeks after midsummer. This isn’t the journey that I made then, though it is the same route. I remember everything. I remember nothing. Upwind. All the turbines facing north.

Two more swans, winding into the west, like the first pair. Maud’s Bridge. I lean into the light of the lone house on the south bank and make a note of the swans, and the rotational direction of the turbines, and something I’d forgotten, one hour back, the water tower at Thorne, an unlit cutout.

I know the OS map as well as I know the ground. Sheet 112. I leave it in the back of my rucksack. The bridge is a reminder that the county border is close, a mile, less than a mile. South Yorkshire. North Lincolnshire. The canal draws level with the railway. A single red light just ahead.

11.09pm. Wind shear at the edge of Thorne Waste. A dozen or more turbines scattered between two counties. Tinnitus whistling to itself. One note perpetual. Not so much pain as discomfort. Manageable for now. A two-carriage train arrows into the west. A single green light in the distance.

What if the body is a threat to the body. How can it defend itself. Against itself. There are no threats here. There is only the wind. The wind moving the rotors and blades to the north. The wind stirring the winter grasses and the reeds in the soak drain. The wind at my back.

11.25pm. Two swans. Westward. In silence. I remove one glove, then the other, and scribble a note, three sentences that I can’t read. I slip the gloves back on and make heat with my fists. Buckles. Zips. All the layers working together. A train into the east. Then the signals: red, amber, green.

11.45pm. Medge Hall. Ten minutes of steadily intensifying light in the north-east. A small white signal box at the end of it. Between the water and the tracks. I don’t cross the bridge, I can see that the cabin is still lit up inside, is someone coming to the end of their shift. Very cold now.

A scattering of houses at the edge of the towpath. The estates are expanding through light: lights in the trees, lights on the gables, lights at the gateposts. The path is diminished. The walk has no premise. Who are you and how did you get here. What are you doing out there in the dark.

Who am I and how did I get here. What am I doing out here in the dark. I thought that I might try to spend some time away from the body. Or thoughts of the body. It isn’t working out. A mobile predicament. An unknown impediment. Circling the abdomen. North, east, south and west.

Midnight. Zero hour. Somewhere around here is the Old River Don, the county boundary before it shifted a mile west, the former channel to the Trent, cutting through Flandrian alluvium, now an unnavigable remnant of the ancient meander, not much more than a trickle, lost between ditches and drains.

12.17am. Godnow Bridge. The signal box is dark and empty and the mechanical barriers are down. The road bridge is open. The railway is closed. Slowness in the shadowed apparatus and almost nothing to the wind. Hours from now, an hour before dawn, the labour of getting the parts moving again.

I remove my right glove and type a message for Emma, letter by letter, into the keypad of a battered Samsung GT-E1230. Good night, it says, sleep well, and words of reassurance, comfort, and safety, something to settle the heart, something to last the small hours. I press send and read it back.

Lights in the east. And what sounds like geese. Massing and clamouring. The water park, the lakeside lodges and caravans, the bright flame of perimeter security. I turn away and stare straight ahead. What can the moon show me. Uneven ground. Patches of frost. The shadows of trees on the towpath.

Noises out of place. A sound I can’t match to a source. Whine and thresh. A turbine, I think, but nothing stands out in the night and there are no wind farms in this pinch point between road and rail. The sound loses strength as I pass beneath the A161 bridge. No way up the embankment.

The unnamed road to the intersection of the A161 and A18. The narrow footway between the galvanised steel barriers and the sinking treeline. The towpath below that still bears my tread. The canal and the permanent way. The little industries in their corrugated sheds. The slow descent into Ealand.

Ten years since I first set foot in this village. I knew nothing of the Isle of Axholme, other than the rail infrastructure that made it possible for me to get here, and the energy infrastructure that compelled me to make the journey. I turn east at the junction as a car races north to Crowle.

1.07am. New Trent Street to the New Trent Inn. The pub is now a private house and the war memorial has gained a flagpole and flag that dwarf the stone column. The post office has closed. The Methodist church has been deconsecrated and converted. The adjacent green is for sale as a separate plot.

Boiler plumes curling from the newbuilds on Main Street. I keep on, past Wraith Farm, past the cartoon reindeer, the rucksack sagging with the weight of the water that I haven’t been drinking, then stop. Outgate and darkness. I shrug off the straps, open a bottle, and take three small sips.

The village at a halt. The cottages, the gardens, the street lamps, it all stops dead. Nothing advances into the east but a pylon line and a service road, a farm track with no farm buildings in sight. Earlier, on the canal, the moon was slightly ahead; now, it has slipped back. It’s enough light.

No trees. And even the pylons are falling away, crossing overhead and receding to the south-east. Drainage ditches at every field parallel, I know this from the maps, but I can’t see them, I can’t hear them. Nothing on the horizon but the horizon. No movement. No depth. No elevation.

Unbounded flatness. A false reading, the hour and the season, the edges of perception dulled by darkness. Darkness and cold. It’s not possible to hold on to anything for more than a few seconds. To pause. To look out. To look up. Draw everything down, close to the skin, studs, straps, seams.

Gas pipeline marker. A stand of trees, squared by a low fence. A set of gates and what might be an energy facility, perhaps a node in the transmission network, LOCATION No 175500 EASTOFT. A battery farm, the long, grey sheds set back in silence, a single continuous sheet of corrugated steel.

Then nothing but the turbines ahead, the merest outlines, scarcely visible, and the picture has no sound. The first dawn at Outgate. I could see them at double the distance and thought that I could hear them too. It took more than a mile for the picture to change. To adjust my sense of scale.

Small white shapes to my left. The other side of the drainage ditch. Sheep. Thirty or forty. And not altogether real. Something in the movement. Skips and gaps. Missing frames. It’s not the sheep. The sheep are fine. On their feet. Facing west. Always in motion and never quite changing position.

When I think that the turbines are drawing near, when I can see the blades in each rotation, I remove my hat, so that I might hear the weight as it rises and falls, the upstrokes and downstrokes, the wake. A star lights the tip of the meteorological mast at the western edge of the wind farm.

No telemetry. No cellular modem. No incoming data. I make a guess at the temperature, the effective temperature, based on what I knew when I set out, and what I think I know now. Call it -8 centigrade. I squeeze through the gap in the SSE vehicle gate. Ice in the potholes, ditches and dips.

The gravel road crunches through the wind farm. When I am within a hundred feet of Turbine No. 13 I stop, lean back without my hat, and look up at the hub, nacelle, rotor and blades. Never so distant as now. Then I look beyond the turbine at Orion. Faint with finitude. The arrays in alignment.

The wind farm is a path to the gas power station at Keadby. Steam and light. Blurring my vision for almost two miles. The site has gained another plant since I was last here. I edge past the single-bar gate that divides the field track from the unclassified road and turn left onto Chapel Lane.

The first of the pylon chains, then the next, and the next, each one anchored to a terminal tower, the other side of a temporary fence. I don’t look up as I pass beneath the lines, I don’t stop to consider the bundled conductors. The faintest hum. Then stars overhead. Lights in the village.

2.40am. The water tower on its concrete pedestal. Almost every house lit from without or within. Two flags flutter from half-closed windows. Three minutes to the end of the lane. I unhitch my rucksack and sip cold water. Smears of grit salt at the junction. The embankment and the tidal Trent.

I scramble up the embankment and look out at the river and the lights across the river, the lights of Gunness and Scunthorpe, the roads to the east. Then I scuttle back to the junction. An ambulance in slow motion, northbound on the B1392, smaller and smaller as it takes each corner.

I follow the route of the ambulance, clear of the village and the outlying houses, the Trent to the west, all of Axholme to the east. The pavement is gone. The road is empty. I walk the edge of the southbound lane. The warping drain and the concrete sluice. Three tall pylons crossing the river.

2.55am. To the north, a meteor, halfway between the heavens and the horizon. It happens in the moment that I lift my eyes from the road. It happens once and once only. It’s enough. To look out without looking. This must be the Quadrantids, named for Quadrans Muralis, an obsolete constellation.

I think of the meteorite in my desk drawer, a smithereen, the debris shed by comet Swift-Tuttle. My great aunt collected it from her farm driveway in August 1962. Over the years it fragmented and she gave one of the fragments to me. A small lump of rock from the constellation of Perseus.

The sign for Amcotts parish. A single green light, suspended above the embankment, slow flash every few seconds. Still nothing on the road, only the road, curving east with the river. The body ahead of the mind. A sense that I am not fully present, that it is only the cold keeping me here.

The mind ahead of the body. Work backwards and worry a method into shape. The conclusions are always the same. Something bad. Something that can’t be fixed. Is there a name for this? Thanatophobia? No. That isn’t it. That’s not what this is. If I could name it, would I understand it?

The things that make up a life. Suddenly they seem so small. This fragment of meteorite, for example. I’ve carried it with me for forty-five years. The memory of the places I once called home. In every flake and fissure. Ordinary. Dull. Not of this world. It rests in the hollow of my hand.

3.25am. Every ten minutes I turn back and see that Keadby has maintained its size with the passing intervals and still no Amcotts ahead. Eventually the lights and a left turn from the river and a sign scarcely legible. The ambulance from earlier is still winding through the lanes at half speed.

The village is almost pretty in the dark. Cable lights in hedges and trees but also the ashlar and slate of St Mark’s. It thrives in the silence. Two bus stops. No other amenities. No directions at the junction. One of these roads leads out and the other two do not. This one. This one. This one.

Guesswork. White lines and tyre marks. Somehow I read it right and set myself on the road to Garthorpe, leafless trees spaced evenly along the northbound verge and, on the other side, the curve of the embankment in near alignment. Widdershins. The isle to my left. Drain after drain after drain.

Flixborough over the water. The steel terminals and solar farms. I tried to make a path through the wharf but couldn’t see my way to the end. Ten years ago. The river turns from the industrial park and the only light ahead is the steady pulse of the green navigation beacons on the flood wall.

4.10am. Thick white glare in the distance. So thick that I can’t read the distance. Then no distance at all. I step into the northbound verge and see it for what it is, at actual size, a pumping station for the Paupers’ Drain, multiple structures, concrete and brick, all sides lit.

What does the body know that I don’t. I have no sense of appetite or thirst but the tissues and organs can’t go on alone. I stop at the embankment and shuck off my rucksack and take out my water bottle. I open the bottle and raise it to my lips and find that the contents have turned to ice.

The turning for Luddington and Eastoft. The pylons as close as I remember. Onward to Garthorpe and Fockerby. Let the mind drift. To no purpose. Reckon the distance. Halfway from Amcotts. Two miles or three miles or four miles. And the same again to Adlingfleet. And the same again to Ousefleet.

4.45am. I can feel the river getting away from me. And nothing in its place. To begin again. A late starter. A slow learner. This is how it goes. The middle years. The heavy losses. Never single. Always multiple. At some point you think you will be next. At some point you will be.

Garthorpe. A brief stop at the eastern edge of the village. A sip of water from a part-frozen bottle. I make a few notes in lamplight then set myself back on the road. Bungalows and semis and one or two smallholdings. A newbuild village hall. A shut pub. No shops. Darkness at the crossroads.

5.10am. Never settling. Ever beating. For what. For whom. How long the histories. How short the memories. Get out. And leave us this. Get out. And leave us alone. To rend our garments. Leave us alone. With our inheritance. Bad nights. Without rest. Bad dreams. Without end.

I get out of the village. An owl calls from the fields. The road bends back in the crook of the land then straightens out again. Alkborough rising in the north-east. I track the green lights and the distant ridge until I see Adlingfleet ahead and there’s the moon right where I left it.

A car from nowhere on my left, heading north, then west, Blacktoft and the causeway. The first vehicle to pass me since Amcotts. Rear lights slow to burn out. A half-familiar sound on the right turn. A half-familiar sound on the left turn. 5.45am is cockcrow in Adlingfleet.

6.05am. A long, low, composite barn, breeze blocks and corrugated sheets, twin silos to the rear. Sparse beeches. Dead-end utility pole. Then nothing but flat fields and an inexhaustible horizon. Moon now in the west. Somewhere over Faxfleet, a second meteor, as unexpected as the first.

6.20am. Ousefleet. I missed the sign for the East Riding. Before or after Adlingfleet. Or nowhere at all. I try to make out the anti-pylon message on a crumpled vinyl banner but the folds are stuck fast. It is cold. Colder than midnight. Windows and gardens aglow. Light without heat. None of it touches me.

The linear villages. On the other side of the Ousefleet sign is the Whitgift sign. Two inches of separation. The space between the settlements has been filled in with more settlement. Walled estates to the west. Strings and clusters of lights in the formal avenues. Still no shops to be seen.

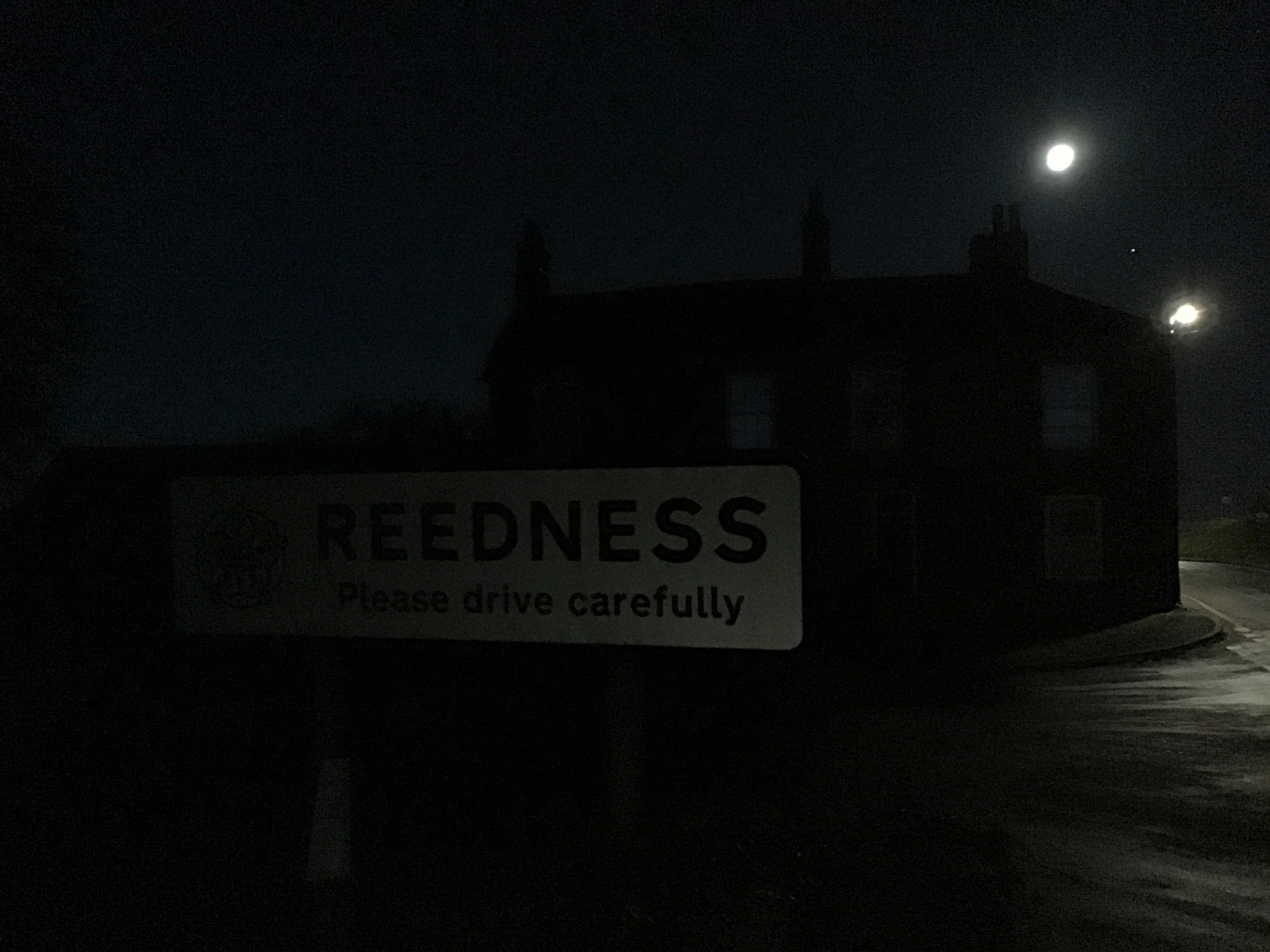

Seven bells chime. As I near Reedness I pass a lorry driver closing a farm gate. He is cheerful and friendly and greets me warmly. He tells me of his journey, how it started several hours ago, in Bridlington, black ice, poor visibility. Happy new year, he says, and turns left at the church.

7.40am. A thin parish to my left. A thin embankment to my right. 10ft walls. 15ft flagpoles. The wind from the west. The Ouse to the north. I could scramble up the concrete steps and look out towards Yokefleet or Saltmarshe but I haven’t the strength. Sunrise in the south-east. An hour too late.

Take down the turbines. Bury the pylons. Dismantle the solar farms. No through roads. At the edge of an island. Within an island. That once was marshland. And will be marshland. Between the floods. Beneath the waves. The sunken networks. The last refuge. Retreat. Retreat. Retreat.

8.05am. Swinefleet. Letting go. On the wrong side of daybreak. Twenty-six hours awake and everything seizing up. The cold gets into your bones. It always finds a way. The light will colour the moors. It wasn’t the dark that I feared. A robin alights on a bare branch. It lifts me out of myself.

8.20am. I scale the embankment and look out at the Ouse and across the Ouse and through the five hundred acres of warp silt known as Sandhall Farm until I find the dockside industries on the other side of the meander. Goole by any measure. The water towers, the grain silos, the parish steeple.

Quay Lane. The outlet sluice and the warping drain. An agricultural improvement plan. Six miles south where the railways ran. Through Field House Farm and Swinefleet Moor. Derelict peat works. Burnt-out stores. East Riding no longer. Lincolnshire neither. Counties bounded by a gutter.

8.55am. I climb the bank to the river wall and walk with the Ouse for a few minutes. One last look. The water rising in the north-west. Emptying in the east. No other certainties. I step down from the embankment and shuffle along the pavement. The moon fading out over Goole. Near transparency.

9.10am. The A161 and the Dutch River. The long way round. The last thousand yards. Bridges, islands and kerbs. Nothing is quite level. The station. The waiting room. Closed. I wedge myself into a corner formed by a cladded wall and a suite of InPost mail lockers. Out of the wind. Out of the world.

This is the third and final instalment of the Dutch River series. ‘Dutch River’, an account of a night walk from Kirk Sandall to Goole, appears here. ‘Unrecovered Time’, an account of a walk from Leeds to Goole, appears here.

This is such a compelling read, I started feeling chilled. Wraith Farm sounds both appropriate and too fey. I was relieved when you finally met the lorry driver; though you may not have been. It's our world from the outside.

Stunning piece, the way you track that unexplained ache alongside the landscape itself is brillant. The body as both transport and obstacle, dunno, it reminds me of a winter hike I did once where frostbite anxiety competed with every step forward. Your decision to keep moving despite not knowing what the discomfort ment feels almost reckless in retrospect, but maybe that unknowing is the real subject here, not the cold or the distance.