Slow Networks

Scenes from the Ridgeway, 28-29 July 2024

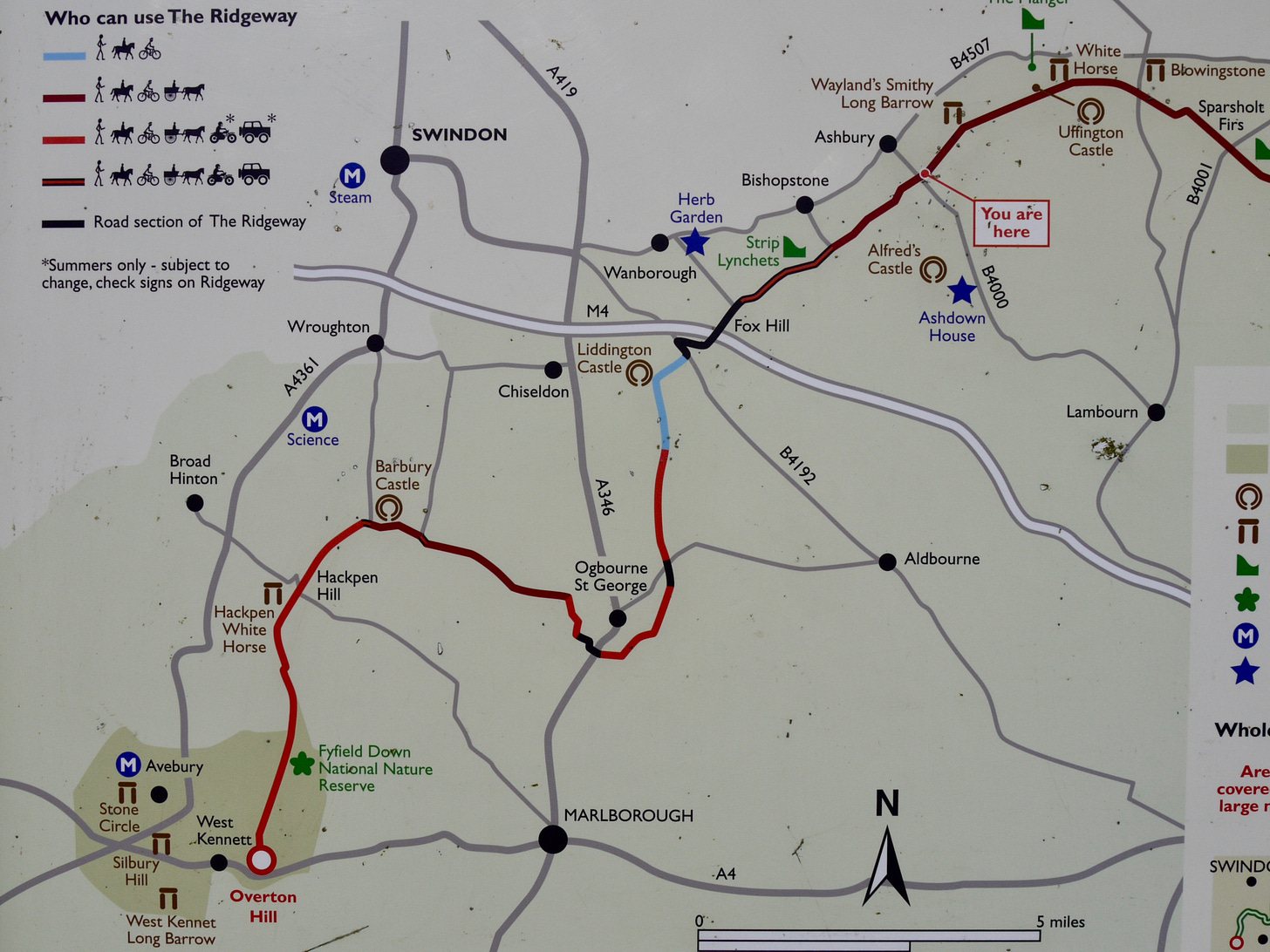

On 28 July 2024, I set out to walk four-fifths of the Ridgeway, from West Kennet (Wiltshire) to Princes Risborough (Buckinghamshire), a journey of seventy miles across four English counties, which I intended to complete in thirty-five hours. Here is an account.

The car pulls in to a layby on the A4. It's Sunday, a little after 7am. I don't drive, so the first stage of the journey has been enabled by Pete, the elder of my two brothers, with whom I have been staying for a few days, and who has spared me a 14-mile walk from North Wiltshire.

I thank him, and haul my rucksack out of the footwell, close the passenger door, and watch as he goes. Then I take in the view from the layby. Silbury Hill is the tallest artificial prehistoric structure in Europe. It's a neolithic chalk mound whose original purpose is still unclear.

There seems to be almost no point in photographing Silbury Hill. How many photographs have been taken from this spot. How to render the scale of it. I photograph it anyway. The River Kennet, a tributary of the Thames, has a source nearby, and also draws from springs near Avebury, a mile north.

I turn from the layby, step through a metal gate and take the path to the long barrow. Wheat on the slopes. Pockets of mist in the vale. More than six months have passed since I was last in Wiltshire. More than seven years have passed since I last set foot in this landscape.

Two walkers. We exchange a few words, are you local, not really, do you know this area, a little. I cross the Kennet and start the ascent. There wasn't time for this last year, a year of letting go, and is this a homecoming, a departure, or neither, or both. I turn and look back.

Southward. Slowly. The path a green lane through uncut corn. Curving upward into air. It is like this every time and every time is the first time. I climb for several minutes without the barrow coming into view, and, for a long moment, the idea of it sinks behind the hill.

Here is the summit, or near enough, and here is the barrow, like a thing remembered. Every time it seems further off than before. Set back or set aside. In cloudless blue. Over 5,500 years old. Older than Stonehenge, older than Avebury, older than England.

I came here as a child. I was seven or eight. I didn't see it again until thirty-four years later. As I approach the blocking stones I realise that the barrow is, for me, a sacred place, because the memory of childhood is a sacred place. And part of it is preserved here.

Years of backward glances. Yet this is only my fourth encounter. West Kennet Long Barrow was the end - the objective, the destination - of the first three excursions. Today, it is the beginning. It's a strange place to start from. It leaves me with nowhere to go.

A journey of several decades to recover two or three seconds, they're still here, in the gap between the blocking stones and the forecourt, on the threshold of the north-east chamber, the echoes of those seconds, when I came to this place for the first time.

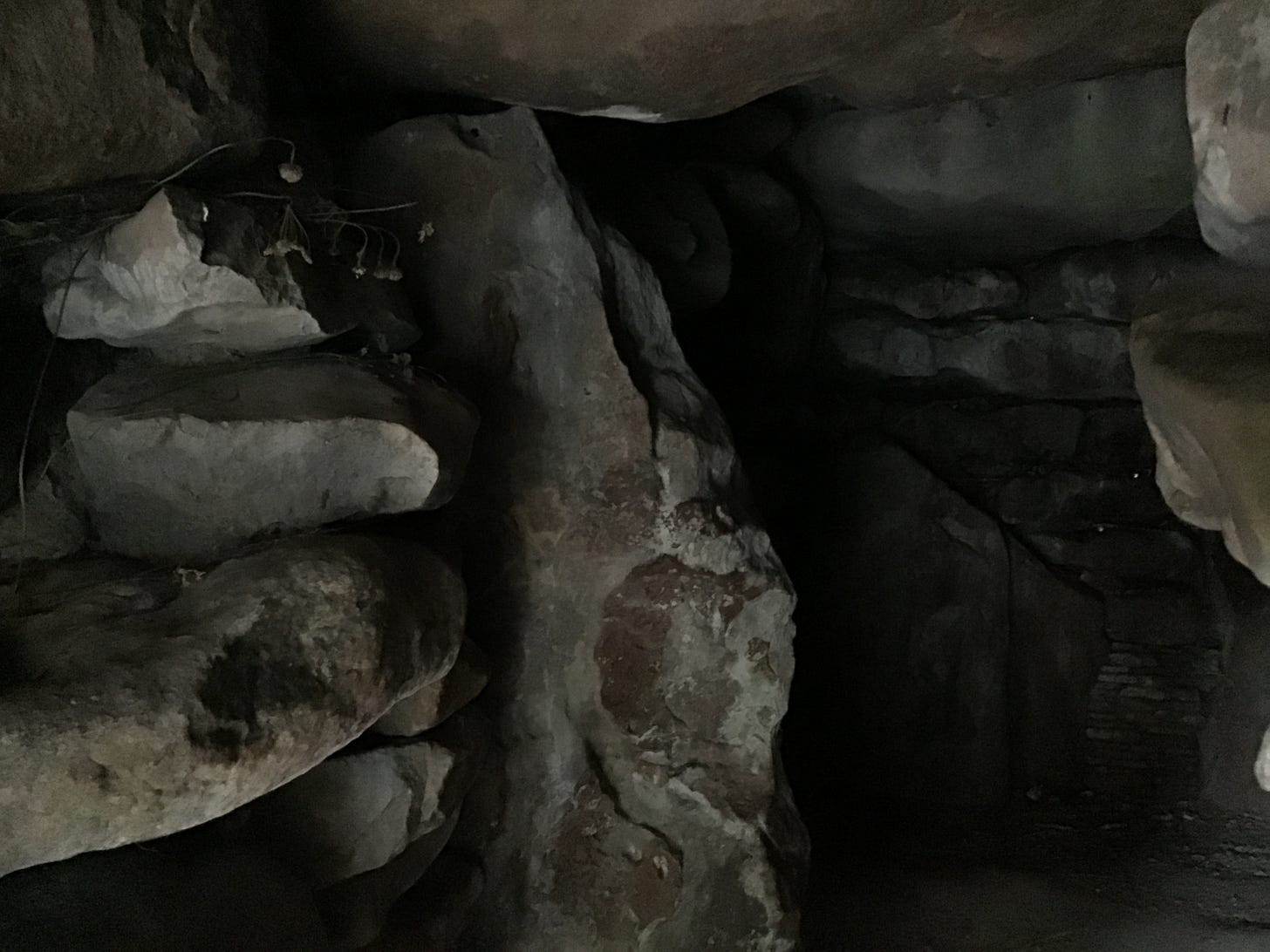

The chambers are built from sarsens and limestone and darkness, tempered, at this hour, by light at the entrance and two small lightwells set into the roof. The roof is high enough to allow visitors to stand upright. I seem to take up no more space now than I did when I was small.

Tealights and wheat ears in the west chamber, dried flowers on the lower ledges. I have brought no offerings. I pace the length of the barrow, back and forth, and then, after a few minutes, stop at the threshold, lost in the play of light on stone.

The light takes its shape from a gap in the blocking stones and prints itself on the floor of the barrow. Time passes. The light holds its shape. It's an old shape. Old as the oolites. Solid as the sarsens. It has minutes before the sun's arc, or a passing cloud, peels it away.

The light isn't all that crosses the threshold. Swallows burst from the higher ledges, exit the chambers at speed, and make circuits above the grassy mound, working the air, over and over. They have nested here for ten summers or more. There might be chicks. I keep my distance.

Rock as Gloss, Mark Goodwin (Longbarrow Press, 2019). The press was named for this barrow, not by me, but by Andy, the press's co-founder, it was one of several names I put forward, almost unthinkingly, he picked it out, without hesitation. 8.10am. I hold the book to the light.

8.15am. I gather up my things and prepare to leave. As I emerge from a gap in the blocking stones, two small boys, their mother, and their grandfather appear. The boys climb the steps at the side of the barrow and race to the end of the tumulus. Their mother calls after them.

Walking to the hospital, three days before my mother died, it caught up with me then, the realisation that I would not be a father. It wasn't painful, and how could I indulge it, but it was surprising. The end of the rope. To be suddenly unmoored. No sight of land. No way back.

The barrow stretches into the west, eight times the length of the stone chamber, the rubble, chalk and grass embankment receding into blue distance. The swallows are out of the picture. I pluck an ear of wheat from the field's edge and start back down the hill.

The exterior of West Kennet Long Barrow was originally clad in chalk, as was Silbury Hill, gleaming landmarks, unlit beacons, visible for miles around. I turn right at the bottom of the hill, along field edges and farm tracks, picking litter from the hedges as I go.

East Kennett is a small village with few amenities. No shops. No bus service on Sundays. The telephone box is now a book exchange. I settle in the stone bus shelter, write a postcard to Emma, then post it in a wall-mounted postbox. The next collection is tomorrow. Slow networks.

I drink some water and apply sunscreen to my face and neck. I step out of the shelter and place a copy of Rock as Gloss in the East Kennett Book Exchange. Then I fasten my rucksack, hoist it over my shoulders, and walk the half mile north to the start, or end, of the Ridgeway.

9.55am. Overton Hill. The trail arises from nothing, a car park at the edge of the A4, basic signage, no facilities. Two or three vehicles and, at the far end, two men talking over each other. All I see is the path ahead. I don't even notice the round barrows in the east field.

10.55am. Dry, rutted tracks. An uneven ascent. I look west towards Broad Town and Broad Hinton, where my father spent the first year of his life, a little house somewhere off the High Street, he and my brother tried to find it, years later, but drew a blank. The path curves east.

11.15am. Intermittent shade from a scattering of trees. A thick stand of blackberry bushes. I stop, lean in, and sweep. Small, green fruit, weeks from ripening. I cannot, and will not, maintain Longbarrow Press from a sense of obligation alone. A glider overhead, no, two gliders.

11.25am. Clouds massing and dispersing over Hackpen Hill. The trail is heavy with heat. I stop and unshoulder my rucksack and sit to one side of the path and nod as men on expensive bikes joggle through the turn. Water. A few photographs. More water. Uphill on cratered chalk.

11.40am. I stop again, at Hackpen's summit, and try to picture the white horse etched into the western flank. It can’t be seen from here. It wasn’t meant to be seen from here. No ancient, mysterious imprint, either, it was cut in 1838 by a parish clerk and a pub landlord.

The simple shapes of rounded copses. One, two, three. The track descends to Barbury, slowly turning east, uncomplicated, easeful, physically, at least. The route of the old Ridgeway runs to the north of the site; the current national trail rises with and passes through the castle.

12.20pm. I scale the short distance to the western ridge, just above the lower ditch, and rest. I watch the people ascending and descending the path. I think of the hillfort 2,500 years ago, and sixty years ago, when my parents were young, and forty years ago, when I was young.

We came here as a family, but how often, and when, and what did we do here? Did I pace the ramparts with my father? Did I wander off on my own? Did we spread a blanket on the grass and sit down for a picnic? What was in my mind as I looked out at Uffcott and Overtown?

I make a circuit of the north ridge, stopping to photograph a cloud-shadow to the west, the shadow drawing level with a solar farm in an adjacent field. The long path to the car park, a man cradling an exhausted dog, a woman spreading a blanket on the grass, come, children, sit.

The first short cut, avoiding Ogbourne St George, stealing along the old Ridgeway, working out the route by inference. Three miles of arid, pitted byways. Gunshot and echo from the shooting school. Everywhere, the noise and stink of combines, shearing the land from end to end.

2.50pm. The first blackberries of the day. I cross the M4, slog to a breezeblock bus shelter, peck at my rations, then pick up the bridleway. This is the other sort of midlife crisis, not capriciousness or delinquency, the realisation that the things that used to work are not working now.

3pm. Foxhill to Odstone. I still think of this section of the trail as local. I'd set off early from my mother's house and head east, through Badbury and Liddington and into Oxfordshire, turning back at Wayland's Smithy, the limit of a day's round walk. I can't do that anymore.

I can't go back to the place that I started from. I knew that when I left my mother's house for the last time, the house that my father built sixty years earlier, the house that was home to us all, I knew that when I handed over the keys. No more departures. No returns.

3.30pm. 25°C, perhaps, an estimate, I can't be sure. Heat mitigated by broken cloud cover and irregular corridors of hedges and trees. I should be another three miles east by now. I should have taken more water. The minutes lost to calculation, adjustment, resource management.

4.30pm. Idstone Hill. A sign. DRINKING WATER. The standpipe is close to a dilapidated outbuilding and drains into a trough. I refill two empty 500ml bottles and drink another 500ml. Then I wash my hands, sticky with sunscreen and blackberry juice, discoloured by dirt and sweat.

A red admiral, never more than one, is it always the same one, a few yards ahead, rising, settling, fluttering in and out of the dust, the only colour on the bridleway, the only colour in my mind. To step out of your own path, for a moment, to see yourself as a point on a line.

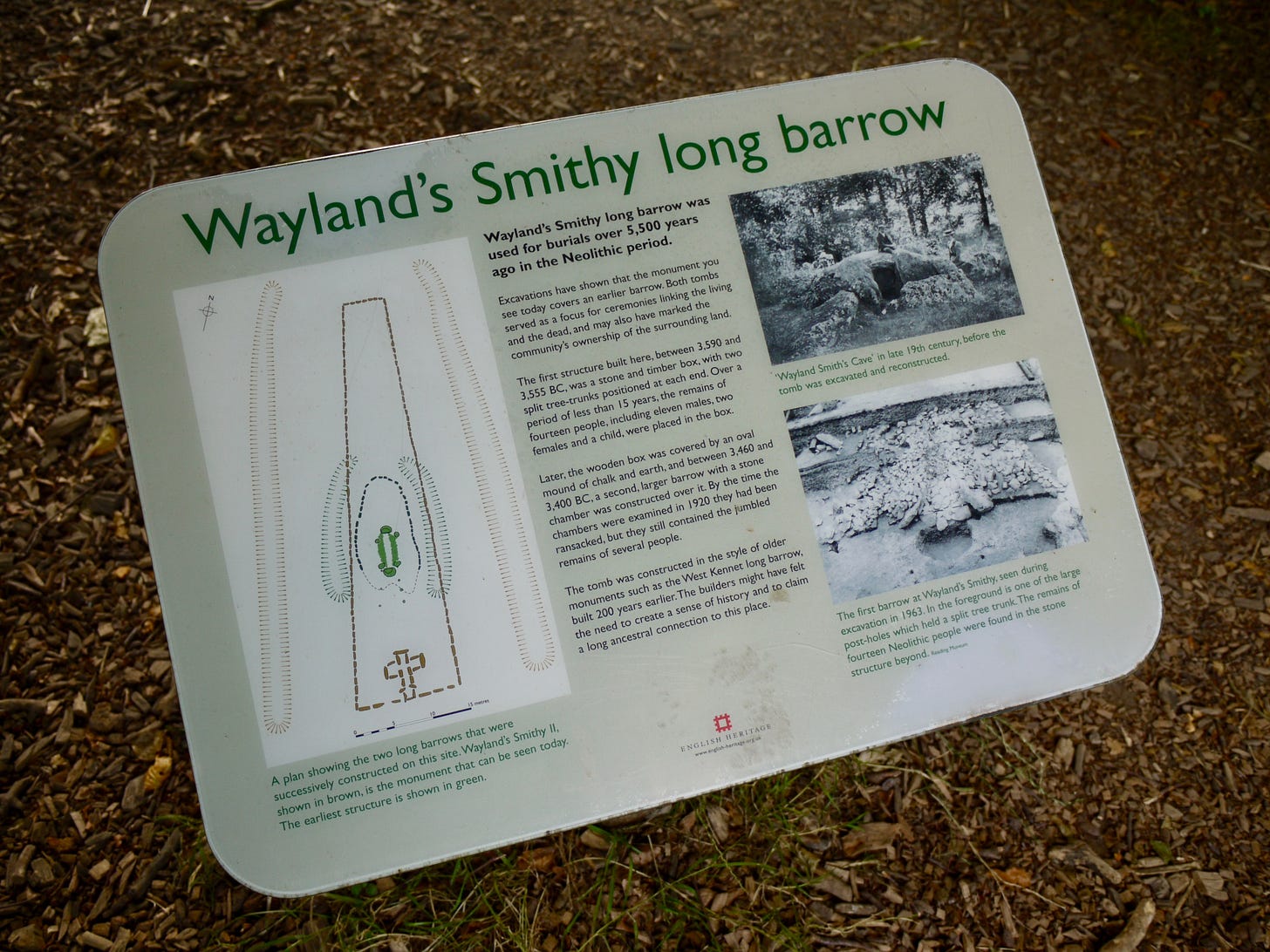

5pm. Wayland's Smithy. The approach to the monument is screened by an avenue of trees along the Ridgeway and by the horseshoe plantation, two hundred feet north of the trail, in which it lies. The light levels drop. The temperature drops. Neolithic theatre.

Work on the site took place a century after the first interments at West Kennet, and occurred in two phases, with the original timber-chambered oval barrow effaced by a stone-chambered long barrow. The last round of excavations took place in the 1960s, after which the barrow was sealed.

The threads of folklore and myth woven into the site derive, in large part, from its name, attributed to the Saxons, who settled here 4,000 years after the barrow was built. When I was last here, in 2019, there were reports that neo-Nazi Wodenists were using the site for rituals.

I didn't encounter any neo-Nazis that day. The only other visitor to the site was a sprightly naturist, who scaled the mound and communed with the sun-warmed stones, somewhat ostentatiously. There are no neo-Nazis here today, either, just me, and three people quietly taking photographs.

I make a slow, clockwise, three-quarter circuit of the barrow and lay my rucksack and my body against the soft, grassy incline. I close my eyes. Forty winks. It isn’t much but it's enough. I come to, slowly, and watch the contrails of a plane dissipate overhead. 5,500 years.

Water. Food. A few minutes with the map. Then I shoulder my rucksack and leave. I think of Friday's visit to my aunt Barbara, at the nursing home in Faringdon, six miles north, her family reproaching her for her stubbornness, there’s a lot to be said for stubbornness, I replied.

6.30pm. Uffington Castle. This isn't my first time here, though, as with Barbury Castle, I can’t summon a particular memory with which to place it. I'm walking this route to piece together a landscape that I've known since childhood, intimately, discretely, fragmentarily.

We would have made our way here by car, as with most English Heritage sites, how else would you get there. Bishopstone and Ashbury and the signs for the car park. The white horse on the north flank. I can't see it from here. I descend to the ditch then climb to the rampart.

Nothing from the rampart. People make circuits of the Iron Age hillfort, in silence, in conversation, working things out in the evening air. I turn back and take two quick snaps of the trig point. A small boy races ahead of his family and declares I AM THE KING OF THE CASTLE.

7.40pm. Sparsholt Firs. I stop at the Hill Barn standpipe, the day's second water refill point, and perhaps the last. This journey has been made viable by two taps. I know nothing about the people who installed them, the people who maintain them, they both run close to farms.

This tap, like the first, has a trough directly underneath, and the signs indicating their position and purpose are partially obscured by clumps of brambles. I drain the last inch of a 500ml bottle, then refill it, and drain that too. Stillness. The long fade of summer evenings.

Two paragliders overhead, drifting near Uffington, engines audible for miles. A stone in the brambles. The tap is placed in memory of Peter Wren, aged 14 years. ‘He loved the countryside.’ No dates. I turn away and look out into a landscape in which Peter is always 14 years old.

I eat two Welsh cakes and text Emma as the sun sinks behind the hill. Midges cloud the standpipe and the brimming trough. I consider the radio station to the south-east, it was my marker for the last mile, everything lined up with the map. The horizon is what you walk towards.

8.35pm. The evening is losing its colour. The downs roll away to the north. I am thinking not so much of the path that I am on but of the path ahead. I am spending less and less time taking in the landscape and more and more time studying the map. What distances to come.

9.20pm. Civil dusk. For two miles east of Gramp’s Hill the trail is broad and soft, brittle, smooth and broken, and all of it chalk, and all of it white. I pick up a powdery chunk and pitch it. Intact on impact. I store two smaller pieces in my rucksack. Samples. Or souvenirs.

10.35pm. The path reverts to a rural byway, forking off into farm tracks here and there, I squint at the signposts, where there are signposts, and squint harder at the map. Low hedges. Low fences. I can see, now, the benefit of head torches, any torches, any light at all.

10.50pm. The path is navigable. The map is unreadable. Half a mile east of the B4494 my trance is broken by the sudden intervention of an obelisk, a few yards from the trail, rising some 30 feet from a square, stepped plinth to a budded cross, half-concealed by bushes.

The map marks it as a monument. What is it and what is it doing here. In the middle of nowhere. In the middle of the night. I circle the obelisk but find no explanation. I sit on the steps and eat salted peanuts and watch as stars appear in the unclouded sky. There is no moon.

11pm. Combines blazing to the south, LED beacons lighting the fields, and fireworks, spherical fireworks, to the north, near Harwell, where a cluster of sites, edged with bright white light, is also visible for some miles. Moonrise, at last, a hazy, reddish moon, waning crescent.

11.20pm. The trail splits into three paths. One path takes a sharp left and tacks downhill. A second path lies straight ahead, along a field edge, overgrown and narrow. The third path, straggling through a gap in a fence, runs parallel to the second. The map is no help. No signs to be seen.

I take the third path on instinct. It winds through a small copse, a clearing, and a car park, and across a minor road to another car park, a double of the first, open to the sky, unsheltered and unscreened by trees. A crossroads and a summit. It is midnight. I will sleep here.

I set my rucksack on a patch of grass and rummage inside and find two bin liners and spread one on the level ground and put my legs inside the other. I locate the bag with three days’ worn clothes and plump it into a pillow shape. Then I pull a thin fleece over my thin shirt.

The bin liners have 30% less depth than I expected and the liner in which I lie extends only to my knees. I assume the foetal position but any position is uncomfortable and leaves me exposed. The ground is cold and damp. The night is silent. The only sound I hear is me.

12.10am. I shuffle and turn. Within a few minutes I am asleep.

1.30am. I have been awake for some time, forty minutes or so, yawning and twitching and shivering. There is no comfort or rest to be had so I get up. I gather the damp bin liners and stuff them into the rucksack.

I stand and stretch and try to stamp some feeling back into my body. Stars cold and bright. The moon a white sickle. It seems even quieter now than it was when I laid myself down. Perhaps if I listened harder, for longer, I would start to pick things up. There isn’t time.

I clear out of the car park and rejoin the trail, sinking into East Hendred Down, and, minutes later, pass a long, wooden bench, a bench on which I might have slept. It is no use to me now. The land flattens out and seems to empty out and I am a long way from the starlit path.

The map tells me that this is a riding route, equestrian farms ahead, these are bridleways, after all. My pace is broken and slow. Chafing. Blisters. I try not to think about this. I try not to think about time and distance but time and distance are all that is left of this walk.

If there is anything in my head it doesn’t take a lasting shape. The path ahead unchanging. Out on the flat straights. Half a mile and the trail dips into a corridor of bushes and trees, sinking down into the earth, and this is the path under the A34, here is the tunnel. 2.30am.

Black signposts above the field line, I can scarcely pick out the letters. This section reflects the one before, the incline is upward, not down, and the path is straight, and the land is emptier with each step. Hard figments. The path repeats and the thought repeats.

Slow starlit distances. Chafe and scrape. A mile to the intersection, grass gallops branching off the trail, the path is clear but I stop to check the map, stuck on page 25. The turn for Ilsley Barn Farm lines up like it says. Sandy equestrian bridleway. Easy going underfoot.

I am beginning to tire. I can’t run on starlight alone. 3.45am. The path is narrowing, steepening, splitting. I stop at an intersection and prop my rucksack against the fingerpost. I scrabble for a bin liner and spread it under the rucksack. Then I slump against the rucksack.

I will rest here, five minutes, ten minutes. I drink water, doze, thumb the map. 4am. I stand up, slowly, reluctantly, gather my things, buckle the rucksack. The sky is lightening. Another moment with the map and all the hard simple distance between here and Streatley.

Almost none of it stays with me for longer than the seconds that it takes to pass through it. The trees and hedges that line the path are just so much stock scenery. The thought of being done with it and all the places to come. The sky gets lighter and my body gets heavier.

Page 28 of the map. I see the first few detached houses and cottages appear, in print and on the ground. Everything starts to look expensive, even the views, especially the views, and I try to set my pace to the wooded ridge that rises to my left, the higher ground to the north.

5.40am. Sounds of traffic, the A417 coming down from Didcot, the trail merges with it, everything runs faster into town. Streatley. The first settlement I’ve passed through since leaving East Kennett. This must be West Berkshire, or part of it, when did I walk out of Oxfordshire.

The trail and the road are absorbed into the A329, more speed, more flow, quickening, narrowing, then shearing off as I make a left turn for the river and the railway. I stop at a bench that backs onto a park and unshoulder my rucksack and sit there, mindless, exhausted. 5.50am.

I drift without quite dozing off. Breakfast. I thumb the map and drink some water and eat a Welsh cake and an apple. All of this takes longer than it should. Everything is taking longer than it should. A cloudless morning, moon still visible. It is 6.20am when I rise and leave.

Slowly, painfully, those first few steps, the kind of pain that you forget until it is upon you again. As I reach the bridge I am learning to walk with it and if things were simpler the Thames, on the approach to Goring, might lift my heart, look, an island, a lock, a weir.

I turn left, and north, along Thames Road, here is the black fingerpost, north for several miles, now, the street runs out, the path runs on, narrow, tree-lined, parallel to the river, then threads into a minor road, and the Ridgeway seems lost in all this, the route makes no sense.

On the grassy trail to South Stoke I stop, for two or three minutes, to photograph the electrified railway as it runs close to the path, hedged by a buffer of saplings in tubular plastic guards. These are the first photographs I’ve taken today and perhaps they will be the last.

I text Emma. Time is getting away from me. The path is a sequence of corridors. South Stoke, eventually, the trail hangs left on Ferry Lane, the river again, between the lane and the bridleway a small waterside clearing, and I slump on a bench, nodding forward and back. 7.30am.

Moulsford across the bend. I lose and recover sight of the river. I see eight rowers, in training, moving south at speed, then, a minute later, eighty greylag geese flying north, high over the Thames, then low, landing on water, and the noise of them, the air-splitting noise.

I pass under a viaduct and pick a handful of blackberries and eat them as I go. The path draws back from the river and winds through a churchyard and I make for a bench set against the walled end. 8.30am. Burnout. It doesn’t seem recoverable, between here and the distance ahead.

Water. Nothing more. I close my eyes. I stare straight ahead. At nothing. At the empty water bottle. A woman enters the churchyard via the lych-gate, good morning, she says, good morning, I manage to reply. Light footsteps. Heavy keys. She opens the main entrance and goes inside.

8.45am. She locks up and turns back to the lych-gate. ‘I’m sorry to bother you’, I begin, ‘but is there a standpipe or tap nearby where I can fill my water bottle?’ There isn’t, but she invites me to walk with her, and unlocks the church again. I follow her in.

It is an old church. There's scarcely time to take it in, the oak roof trusses, the font, the pulpit, it is hard to date, and then I see the pre-Reformation paintings on the wall above us. She opens a cool box, takes out a bottle of water, then says: ‘Is one enough? Here, take two.’

The bottles were intended for the morning service, but she wants me to have them. She asks no questions. I tell her that I have been walking, nothing more, this is not a pilgrimage. I offer my gratitude. I stow the bottles in my rucksack and make a slow turn into Church Lane.

North through North Stoke. Out on the bridleway. A mile of golf to the east. I encounter no-one. A few detached houses at Mongewell and then the Ridgeway turns east, sharply, close to the A4130, passing through a fragmented wood, the shade is welcome, the carriageway unfiltered.

I emerge from the wood at the junction with the A4074 and sprint across the junction and pick up another path as it slips behind trees and opens a new corridor. Then another, smaller junction, farm roads, field tracks, all pointing the wrong way. I rejoin and recross the A4074.

I take a few steps into a bridleway, also pointing the wrong way, I know this, it is a space in which to stop and rest and think with the map. This isn’t the Ridgeway, I know this too, this is the start of a short cut. 9.30am. I have twenty miles to make in less than nine hours.

My walking pace has dropped to two miles an hour or less and I am cut and crushed by all that I am wearing and carrying. The short cut runs on minor roads east of Wallingford, then picks up a few sections of Swan’s Way and the Chiltern Way, it is as straight as I could make it.

Two days ago, I learned from my uncle that his grandfather had a shoe shop in Wallingford. It doesn't add up. Twelve years in the Middlesex Regiment and the Royal Artillery, the discharge, the move to Lambourn, the move to Swindon and the labouring work. The timelines are out.

Half a mile north-east. No pavement, no path, so I walk on the verge as the cars and lorries roll past and on the road’s edge when the traffic breaks. It’s a tonic for the senses, walking against noise and metal and rubber, it resets my instincts. You can’t dawdle or lose focus.

Crowmarsh Gifford. A busy roundabout. The exit I need is straight across, a minor, unnumbered road. I stop at the edge of the eastbound road that separates me from Clack’s Lane and a motorist slows and nods and I scuttle across and land on the other side. Dust and fumes and heat.

It wasn't my uncle's grandfather who had a shoe shop in Wallingford, it was his great-grandfather, William James East. He was there a few years ago, my uncle, he said that the shoe shop was still a shoe shop, halfway along St Mary's Street, in the shadow of St Mary-le-More.

Uphill, slow, northeast, slow, the gradient and turn, the GRUNDON lorries, I will not always be visible, in all this traffic, and the hill and its curve are one continuous reading, section by section, the road is there to be read, when to step out, when to step back.

Another mile uphill. The first of two approach roads for Clack’s farm, this is not the delivery entrance, HGV and Farm Traffic Next Right. I slump behind the sign and set my rucksack against a tree, my back to the road, sheltered from the heat and the passing cars. 11am. 11.10am.

I hear something coming down Clack’s drive so I gather my things, shoulder my rucksack and clear out of the turn, there is nothing there but I ought not to be here. Uphill again. Glimpses of the farm on my right. The incline softens and flattens and one by one the obstacles fall.

A white fingerpost. A nameless road that looks like a grainy copy of Clack’s Lane. Level skies and GRUNDON lorries. After five or ten minutes the depot appears, the road widens and runs straight through it, a split site, lorries exiting from the left and pulling in to the right.

A large blue sign staked in the verge of the north gate tells me that it is a materials recovery facility, and that there are landfills, and I think about the particular situational requirements of waste management sites, how they seem to call for both height and discretion.

The thoughts are soon worn to nothing by exhaustion and uncertainty and flat heat. Almost no traffic now. Slow tread. I can’t keep anything in my head for more than a minute. Distance. Route. Pace. I’m not thinking anything through. I’m not taking anything in. There isn't time.

The road climbs. I stop at a junction and lie on my side and stare at nothing. A cyclist glides uphill. The second day carries its own weight and the weight of the first. At some point I will start to fall backwards. 14 miles at least. And midday now. A mistake I can’t fix.

Upward a half mile. I take the weight of the rucksack with my fingers interlaced behind my back. Icknieldbank Plantation. A small clearing, intended for parking, no benches or amenities, only a fingerpost that tells me that I am following the Chiltern Way. I slump against a tree.

The path lies just inside the edge of the plantation, some respite, at least, and my eye is caught by the white surface detail in a field that lies parallel, is it a flowering, is it chemical or industrial. After ten minutes the plantation peters out. The track runs on ahead.

Ten minutes more and I rejoin the Ridgeway. Another two miles to Watlington. Perhaps 13 miles in all. Is it enough to keep going. I page through the map. I wonder if there are bus services from Lewknor or Chinnor, it is not idle curiosity, I can’t see a way out of this on foot.

The bridleway becomes a metalled lane. One or two men on bikes. And me. I see Icknield House at the intersection and I slide against its low perimeter wall. Perhaps one of the residents will see me and tend to me and then drive me to the railway station at Princes Risborough.

I realise that I am actively nurturing this thought and so I get up, with slightly more difficulty than before, and hitch up my trousers, which have been sliding down since Streatley, one inch to a hundred yards, and on to the Watlington-Chinnor map symbol, the next intersection.

1.30pm. 11 miles. Or more. The train at 6.38pm. Watlington is off the route, half a mile uphill, again I think of buses, yet cannot visualise a service, one that would be there when I needed it, and got me where I needed to go, or halfway close, and how would I find it anyway.

I take a few steps into the clearing that marks the next stage of the journey and flop against a tree and watch as time burns through the faint display of my Samsung GT-E1230. I doze off and pull back with a start. One or two cars in the car park. Not a single thought in my head.

Another slug of warm water, the plastic bottle almost empty, another litre in the metal flask. The water cools the mouth but quenches nothing, the desiccated lips, the dry, tight throat. Slowly on. Intersection with minor road. What will I remember of this. What will I forget.

Two miles of wooded trail. Then out. The ridge in the distance might be the motorway, I don’t know, I have nothing to measure it against. Imagine these ridings as a short, pleasant stroll, and not paced out in pain. Pain is all I have to work with, now, all I have to think with.

I start running, not in the hope that it will make a difference, but with the sense that it can’t make anything worse. I make up little targets on the path ahead, bumps and tufts, and apply myself, a short stumbling run, each goal is rewarded with and superseded by another goal.

Am I trying to break the path down or break myself down. Intersection with minor road. Another marker. Chafe and burn. The black cutout of the motorway underpass ahead. Chafe and burn. Close the gap between the map and the territory. Motorway sign above me, white on blue, almost legible.

Out of the light and into the tunnel. Cool concrete. Heat blasting through. I stop at the end of the underpass and prop my rucksack against the railing that rises from the edge of the elevated side path. Then I loop my arms through the railing and lean forward, my head hung.

3pm is gone. I can’t get it back. Warm water in warm plastic. Slow manoeuvre through the straps and out. Open flat trail then a slow curve into a wooded corridor. The conditions are immaterial now. Annihilating light, cloud cover, tree-shade. I run or walk and still fall short.

3.45pm. Intersection with rural track. I slough off the rucksack and lie face down in twigs at the wooded edge, resting my forehead on my forearms. Almost instantly I doze off. When I come to, five minutes later, I have nearly no sense of how I got here, or from which direction.

It will come to me, when I stand up, and look around, the direction in which I should be walking, it will be obvious. I look forward and back and have nothing more than when I opened my eyes. The trail mirrors itself at the intersection. The fingerpost doesn't help. I don’t know.

I have a weak hunch that the way is to my right. I start walking before the doubts catch up with me. They do catch up with me, a few minutes later, is that the motorway I hear, rising through the humid air, is this the path I walked twenty minutes ago, laid out in reverse.

I can’t be certain of anything until I reach the next intersection, a minor road, a little house, a vehicle gate, none of which I have seen before. Half a mile to the edge of the map, to Chinnor and the chalk pits. 4pm slipping away. The odds lengthening or shortening.

Run walk run. It isn’t hope that keeps me going. Chafe and burn. It isn’t adrenaline. Is it fever, the sense of sinking further and deeper into a disordered dream, incoherent, inescapable, with its own inexorable, incomprehensible drives. A hall of mirrors. A trail of dust.

4.30pm. South of Chinnor. I have been swaying and rocking in the twigs and leaves of the clearing for fifteen minutes. I doze, on and off, I check the time on my phone, one minute, one minute more, and ten minutes pass, if I had another ten minutes. An hour lost and no plan.

4.39pm. I know that it is almost too late, that I have almost certainly blown it, and I stand, still exhausted, and strap myself up and start to push against myself, this is part of it, then, going against everything that your body is telling you, everything that it can give you.

I run, to the quickly made-up marker, the third tree along, then the next marker, the fourth tree along from that, and so on, not knowing if it makes a difference. Climbing through woodland on curving tracks. The valley side sweeping up from the west. Small houses on the ridge.

Here are the kinks in the bridleway, trails branching off, cling to the fingerpost, onward for the Ridgeway and the Icknield Way. Tightly wound between rising contours. A path like a closed loop. I am thinking that I have lost the turn when I see it. And the last of Oxfordshire.

5pm. It is the Icknield Way that I take, for the mile or more that it will cut from my journey. A well-laid, wide-open byway, downhill, dead straight. Three miles, more or less. I am taking nothing for granted and use the hill to run with, the lungs are working well at least.

After half a mile the byway gives way to a road junction, which I cross, and the Icknield Way is now the Upper Icknield Way, and a road like any other. Downhill, still, no pavement, cars and vans behind every hedged or tree-lined curve. I stare them down or use my wits.

The Icknield narrows to a lane, fewer cars, more shade, it dips under a railway bridge then climbs out of its hollow, breaking into light, another bridge, this one spans a second railway line. I canter to the other side then unclasp my rucksack and fall back into my own sweat.

5.30pm. Three minutes at a standstill. The pain is not far behind. Uphill as the trail curves. A potholed turning circle and a field path stretching away. Is this the Ridgeway, am I to turn back, then I realise that I am ahead of it, the Ridgeway is feeding into the lane.

Downhill, now, gently, and levelling as the trees recede, a few houses, tidy lawns and verges, white fingerpost, Shootacre Corner, bear left onto Shootacre Lane, breaking off from the Ridgeway, turning away from Princes Risborough, the road to the station, the road north and out.

Long driveways. Low walls. Telegraph poles staked in the grass and wheelie bins stationed every fifteen yards. I walk in the road, on the other side, until a pavement opens up ahead. 5.45pm. I felt something lift when I stepped onto the Icknield Way and I am certain of it now.

Picts Lane, again the spacious houses and drives, and I can hear the station announcements, now, the high tones of passing trains. The thatched cottage, the little signs for the railway, left, another left, and it’s there at the end, the station, the car park and the far horizon.

The station doors open and the passengers flood the approach, some heading for the car park, some hailing cabs, and I limp on, against the flow, through the station doors and into the waiting area, a long metal bench, mine alone, a small, quiet corner of the ordinary world.

6pm. Half an hour to spare. I text Emma. I’m OK, I’m here. A draught of water from the metal flask. A question, always the same question, what is it that I want, now, at the end of the journey, at the edge of oblivion, the answer is always the same, milk and sleep, nothing more.

This is very easy to relate to, for me at least. I grew up in Abingdon and Wantage, visited Avebury and Uffington and remember these landscapes well as a teenager. I have also done a similar thing, heading off down trails without sensible planning and enough rations.