Inventory

On 19 years of Longbarrow Press

Longbarrow Press was launched at The Red Deer, Sheffield, on 27 April 2006. Here are some reflections – anecdotal, aphoristic, archival – on the ethos and evolution of the press. What we do, how we do it, why we do it. In no particular order.

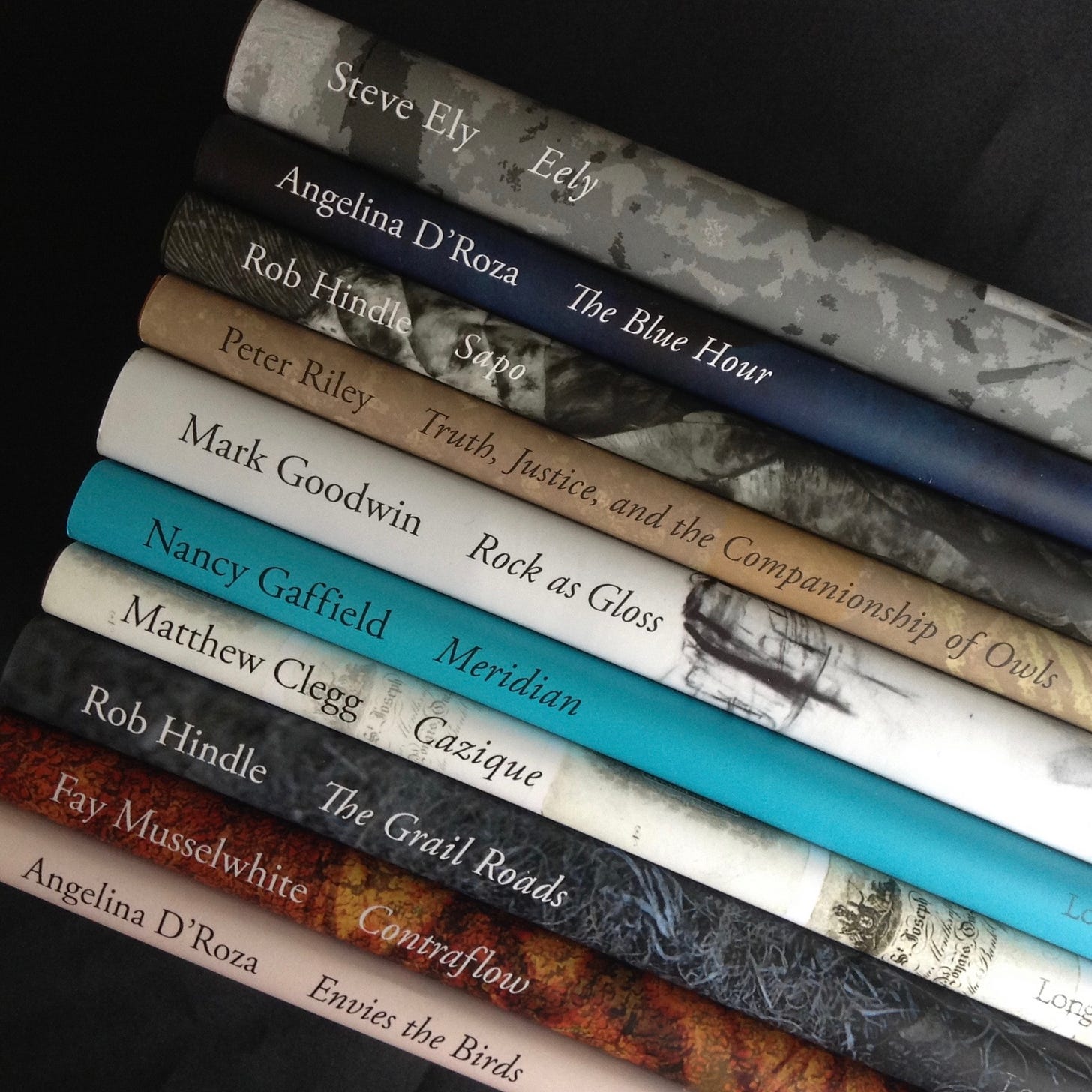

I'm not going to single out books and pamphlets from the last nineteen years, as it doesn't work like that (from the perspective of an editor/publisher). None of the books are possible without the others.

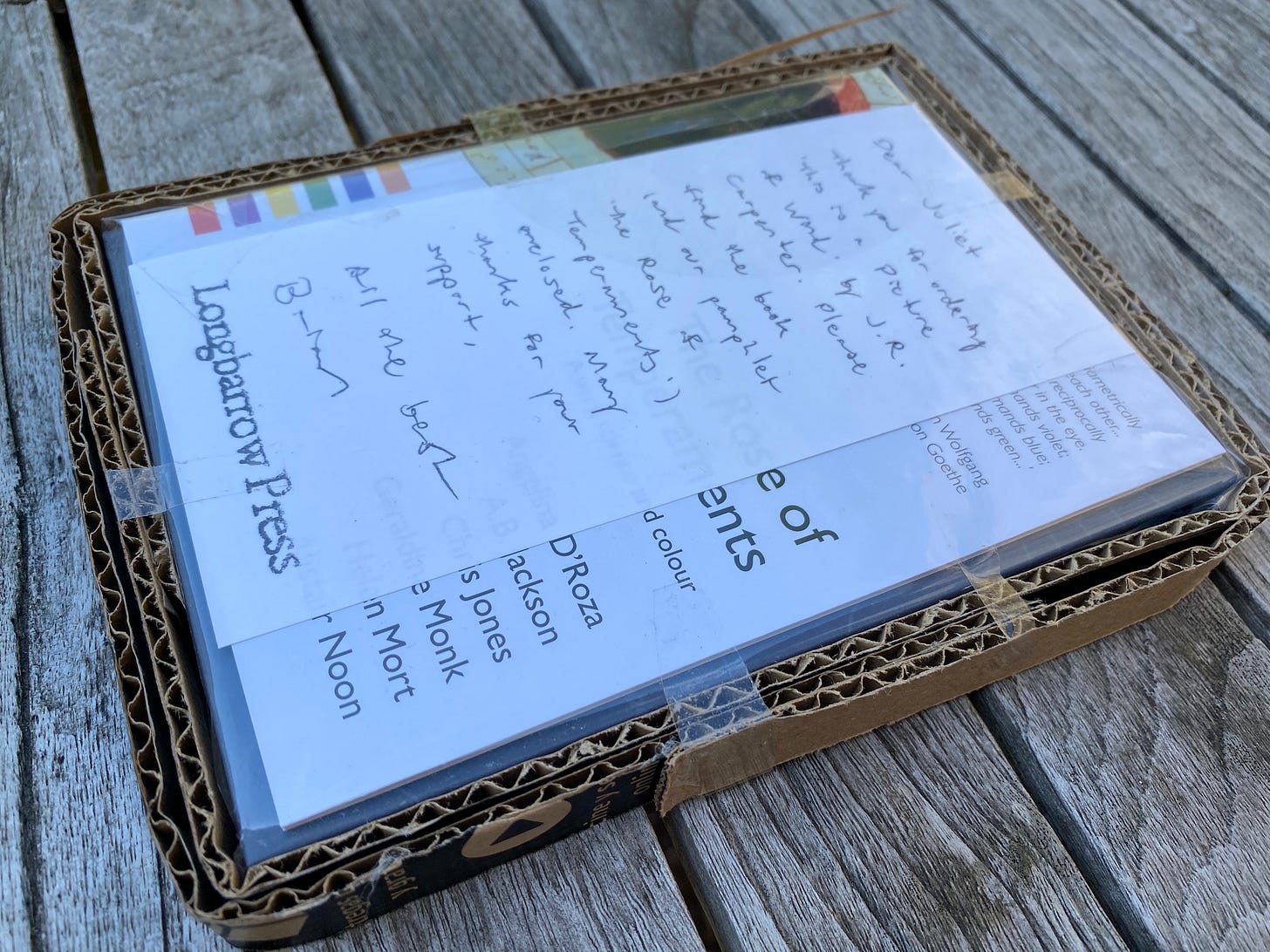

I think of the press as a collective, and in many ways it is, but most of the time it is one person in a small, cluttered room of a terraced house, searching for pieces of cardboard with which to insulate a book in preparation for its journey through the postal network.

The Longbarrow office chair, acquired for £1 in the 1990s, and now, after several decades, past expiry, yet still in service. Is it stubbornness, stinginess, or sentiment that keeps it from the scrapheap. The chair is held together by two bent screws and a buckled metal plate and falls apart every few days.

A small press in a small room. The books take up most of my time, but, even now, take up very little space in the world. It is possible, and perhaps desirable, for a press to develop without 'expanding', without increasing its scale or reach. It keeps things in perspective.

Publishing and the autodidact. I came to this without any industry experience or demonstrable skills. I'm still taking the long way round, learning what I need to know as I need to know it. A slow, indirect route. Almost none of it is teachable, but most of it is shareable.

I edit, proof, and design books to the best of my ability, a process that can take weeks, months, or years, and the proof is in the design and the design is in the edit. Publication is the letting go of all I've learned, the end of something, the beginning of something else.

I dream in fragments of Rhapsody in Blue

the opening phrase never descending

to answer its own question. I dream in notationsof wildflowers, the iolanthe’s quiet dissent

against the clamouring larkspur, the Shepard Tone

of time in dreams, rising, always risingFrom 'Correspondences: The Rhododendron Tree', in The Blue Hour, Angelina D'Roza (Longbarrow Press, 2023)

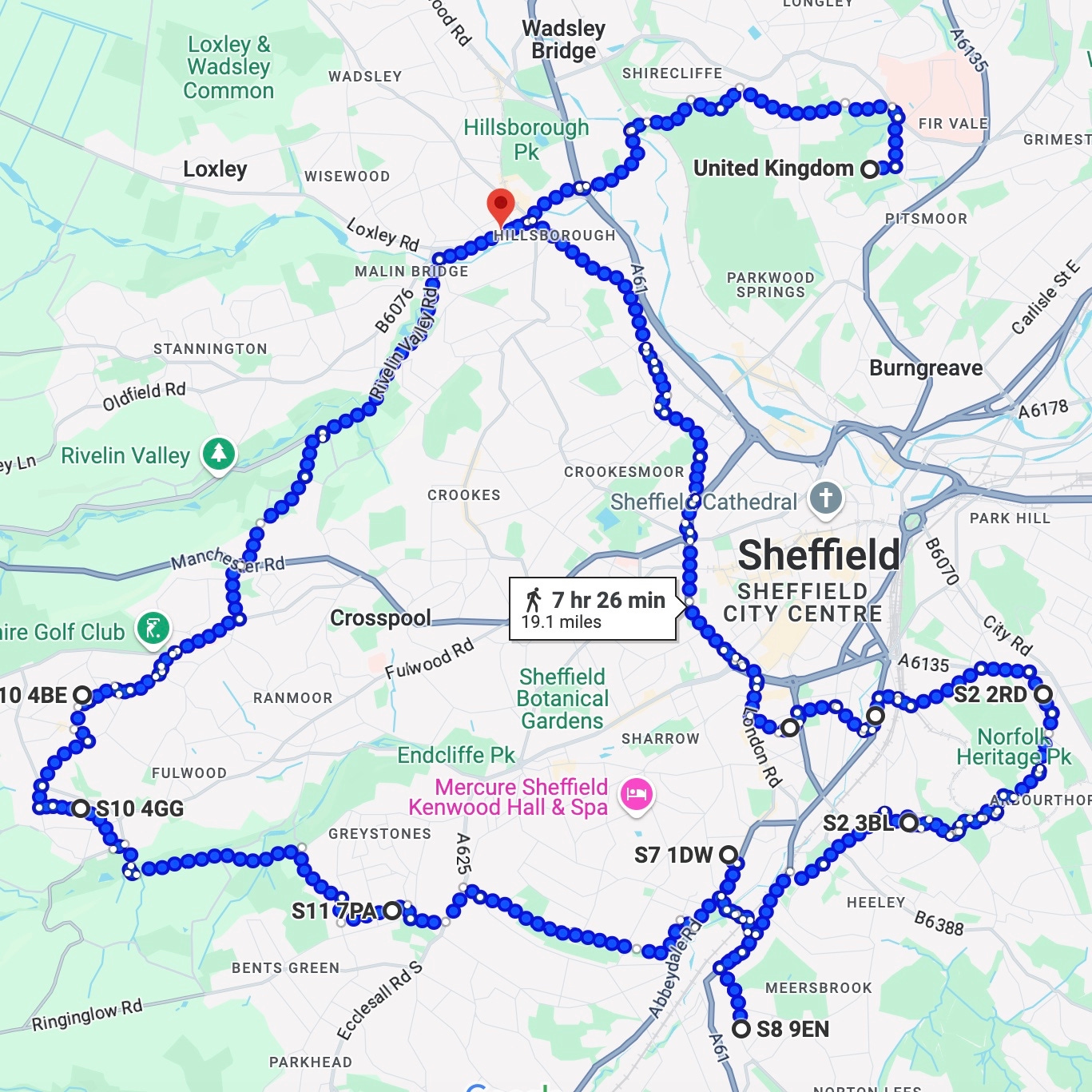

We've presented some interesting and memorable events in galleries, chapels and poky, creaky pubs, but I think we're at our best when we're working outdoors: making notes, taking photographs, or gathered in a collective act of walking and speaking and listening.

The anxieties of 'event management' are largely immaterial on a poetry walk. It doesn't matter if only three people turn up. It doesn't matter if those people know each other or not. It doesn't matter if no-one buys any books. There might be rain. That doesn't matter either.

The poem moves through the world. The world moves through the poem. We move through the world together, and alone, and each of us will perceive it differently. Birdsong, blossom, wind. The poem is only one aspect of this sensory field. This makes it easier to hear the words.

Matthew Clegg led the first Longbarrow poetry walk in 2008. Four years later, he was invited to lead a navigation of the Sheffield & Tinsley Canal, as part of the inaugural Festival of the Mind. An audience of 20 walked with us from Victoria Quays to Tinsley, where the canal meets the river Don.

I'd like to present a 3am poetry walk, though I suspect this would be undone by various organisational challenges and the likelihood that no-one would turn up. Other Longbarrow events that almost certainly will not happen include a reading in a sea cave at Flamborough Head.

Daybreak in the wreck of Dogger. Gulls drifting

over the slowly rising sea. Seals hauled out

on sandbanks, bleached ribs of stranded whales.

Dunlin and knot, swarming the mudflats,

armies of silt-spearing godwit and whaup.

Butterbumps booming from brackish phragmites,

gorged on the bootlace bounty. Harriers

quartering over. Campfire wisp from the holme’s relief

in the pearl of the roseate dawn; boat slides

from creek into tidal waters, trailing

its fuchsia ripple. Paddles out under chatter

of pinking terns, the flushed conflagrations

of billionfold gyring flamingos.From 'Storegga', in Eely, Steve Ely (2024)

With hindsight, scheduling a poetry walk, an exhibition, and a performance all on the same day (as we did in November 2008) wasn't the sharpest instance of event management (as I conceded while assembling parts of the exhibition in a moving van, en route to the venue).

The spaces of transport enabled the completion of a considerable amount of work in our first five years. I remember trimming and glueing the inserts for a publication by Mark Goodwin on the vestibule floor of a Plymouth-bound train as the aircon failed and the lights went out.

I remember hand-stitching Lee Harwood's pamphlets on a semi-darkened National Express coach at 4am while in the early stages of gastroenteritis. I remember batch-cutting 200 event flyers with a portable rotary trimmer on platform two of Cheltenham Spa.

Sometimes the machinery seizes up. In 2019 we published four titles. In 2024 we published one. There are various reasons for this, including sharp increases in printing costs during the last few years. A Longbarrow hardback is 83% more expensive to produce than in 2019.

Time and money. There's another factor, though, one that is arguably more significant in determining the survival of a small press. Morale. The most damaging outcome of a steady decline in sales is a rising fear that the work is not good, is not needed, is not worth the trouble.

On a bad day, in a week without orders, it can look like this: "Small presses are like self-built cars, speeding into a distance of their own making, powered by the steam of their invention. Eventually they break down, in the middle of nowhere, and have to be abandoned." Do I believe this, even on a bad day?

Somehow it's always worth persevering with, even when it doesn't quite work out. One journey leads to another. Even if the journey terminates in a book fair where two books are sold in two days. Two books found two new readers. Chance encounters. Unexpected discoveries. The work is an end in itself.

The end of the work is the possibility of connection, that the book, if it has been made well, might become 'a site of exchange' (to repurpose an idea from J.R. Carpenter), that it might have use and value to others, whether the others are many or few.

A book is a record of process, or processes, textual, temporal, material. It is made out of the world and it makes its own world and it makes its way through the world. Each of these worlds is imperfect. Nevertheless, the possible book shows me that another world is possible.

The publisher's fear of the pallet. The book is no longer a possible book, it is an actual book, with all the imperfection this entails. I lift the boxes from the doorstep and stack them in the hall. To leave them unopened. It is a flaw, to see only the flaws in the work.

The idea of the book. The 'finished' book. Is it ever finished. For days, and sometimes weeks, after publication, I picture the book that might have been, resizing the margins, adjusting the point size, not letting go. The book makes its way through the world. Let it go.

The books go to their readers, one by one, at times quickly, at times slowly, halfway around the world or halfway across the city. There is no supply chain, not as such, only the postal network, irregular events, direct sales to bookshops, and local distribution. Step by step.

Suburb by suburb. Perhaps the last nineteen years have been a dream of a walk from the heart of a city to its edge. The city is never the same city. The walk is never the same walk. Everything turns on the delivery. It's surprising how far you can get on foot.

Thanks to all the poets, artists, readers, audiences, and many others who have been part of this project, and for helping to sustain it through nineteen years of collaboration, craft, and care.

New publications are forthcoming from Longbarrow Press in 2025, including a collaborative work by Helen Tookey and Martin Heslop, and a series of pamphlets by Matthew Clegg. Click here to browse and buy our current titles.